The Evolution of Help from Faster Hands to an Autonomous Workforce

The Unbroken Chain: Tracing the Evolution of Help from Faster Hands to an Autonomous Workforce

We have moved quickly from the helping-hands era to the agentic, autonomous workforce.

Introduction: The Eternal Quest for Leverage

The history of humanity is, at its core, a history of seeking help.

We are a species defined by our inherent limitations—we are not the strongest, the fastest, nor the most durable creatures on the planet.

Yet, we dominate it because of a singular, defining characteristic: the relentless drive to augment our capabilities. We refuse to accept the boundaries of our own biology.

For millennia, “help” was a physical concept. It was the bone needle that sewed faster than fingers, the ox that pulled harder than a man, the steam engine that never grew tired.

The trajectory of human progress has been a steady march away from reliance on naked human effort toward increasingly sophisticated forms of leverage.

We have moved from tools that require our constant, sweating presence to machines that amplify our muscles, and finally, to systems that amplify our minds.

Today, however, we stand at the precipice of a fundamental phase shift. The evolution of help is no longer just about faster hands or stronger backs. It is about creating a synthetic workforce capable of observation, judgment, and independent action.

We are transitioning from an era of using tools to an era of collaborating with agents. This shift from passive assistance to proactive autonomy promises to reshape not just how we work, but how we define the very nature of human contribution.

To understand where we are going—toward an autonomous horizon—we must first understand the long arc of how we got here.

Phase One: The Extension of Muscle (The Era of Mechanical Leverage)

For the vast majority of human history, the primary bottleneck to progress was the availability of physical energy.

If you wanted to build a pyramid, harvest a field, or fight a war, the limiting factor was how many human bodies you could throw at the problem and how efficiently they could convert calories into motion.

The earliest forms of “help” were force multipliers for the human body.

The flint hand-axe was sharper than a fingernail; the spear extended the warrior’s deadly reach; the lever allowed a single person to move a weight that would otherwise require a team.

These were passive extensions of the self. The tool did nothing without the master’s hand, but with the tool, the master became something more than human.

The first great leap in augmenting the workforce was the Agricultural Revolution, which introduced non-human biological help. Domestication was the original automation technology.

An ox pulling a plow was a bio-engine, converting grass into kinetic energy, fundamentally changing the caloric equation of survival.

Society was structured around managing these biological assets, and “help” meant harnessing horsepower in its literal sense.

The Industrial Pivot: Mechanized Help

The true explosion in the evolution of help arrived with the Industrial Revolution. This was the moment humanity cracked the code on decoupling physical work from biological constraint.

The steam engine didn’t just provide more help; it provided a different kind of help. It offered tireless, consistent, scalable power that didn’t need to sleep or eat.

This era redefined the workforce through mechanization.

The artisan, whose value lay in unique skill and manual dexterity, was replaced by the machine operator, whose value lay in tending to the mechanical helper.

The cotton gin, the power loom, and eventually the assembly line were the ultimate expressions of “faster hands.”

Henry Ford’s assembly line is the perfect archetype of this phase. The “help” provided by the conveyor belt system was organizational and mechanical.

It broke complex tasks down into mindless repetition, allowing unskilled labor to produce complex machinery. The human worker became a cog—a necessary, flexible component to bridge the gaps that machinery couldn’t yet handle.

Help was systemic, massive, and overwhelmingly physical. We had successfully outsourced the drudgery of the back, but we were only beginning to address the drudgery of the mind.

Phase Two: The Cognitive Trellis (The Era of Digital Assistance)

By the mid-20th century, the industrial world had a new problem: complexity.

We could manufacture goods at incredible speeds, but managing the logistics, the finances, and the scientific data required to sustain that growth was becoming humanly impossible.

The bottleneck shifted from muscle to brainpower.

Enter the computer. The initial role of digital technology was not to think for us, but to count for us at superhuman speeds.

Early mainframes were industrial-scale calculators that provided raw computational horsepower. They crunched ballistics trajectories for armies and payroll data for corporations.

The Personal Computer as a Mind-Bicycle

The real shift occurred when computing became personal. Steve Jobs famously described the computer as a “bicycle for the mind.” It was a tool that enabled human intellect to move faster and more efficiently.

Consider the humble spreadsheet. Before VisiCalc and Lotus 1-2-3, financial modeling was a tedious, error-prone process done in ledgers with pencils. A single change in an assumption required hours of manual recalculation.

The electronic spreadsheet acted as a cognitive trellis—a structure upon which human thought could grow. It allowed accountants and planners to run “what-if” scenarios instantly. The software didn’t make the financial decisions, but it removed the friction of calculation, allowing the human user to operate at a higher level of abstraction.

This era also saw the rise of connectivity as a form of help. The internet morphed from a communication network into the world’s definitive external memory drive.

Search engines like Google became the ultimate reference librarians, solving the information retrieval problem that had long plagued scholars. “Help” now meant instantaneous access to the sum of human knowledge.

The False Dawn of the Virtual Assistant

As digital tools matured, we saw the first clumsy attempts at anthropomorphizing this help. We got “Clippy,” the Microsoft Office Assistant, who infamously popped up to say, “It looks like you’re writing a letter. Would you like help?”

Clippy was widely reviled for being intrusive and contextually unaware. It was a rigid script pretending to be intelligent. Later iterations like Siri and Alexa improved the interface—replacing the keyboard with voice—but the underlying dynamic remained unchanged.

They were reactive command-line interfaces wearing a human persona. They could set a timer, play a song, or tell you the weather, but they couldn’t do anything substantial.

You couldn’t ask Siri to “plan a marketing campaign for Q3” or “renegotiate my cable bill.” They were assistants that required micromanagement—faster hands, perhaps, but not smarter brains.

Phase Three: The Age of Automation (Doing It For Us)

While personal digital assistants sputtered in the home, the enterprise world began aggressively deploying a more potent form of digital help: automation.

If the Industrial Revolution mechanized blue-collar work, the information revolution began mechanizing white-collar work.

This phase was defined by moving from tools that help us work to systems that do the work instead of us, albeit within very strict guardrails.

Robotic Process Automation (RPA)

The workhorse of this era is Robotic Process Automation (RPA). RPA is the digital equivalent of an assembly-line robot.

It doesn’t possess intelligence; it possesses infinite patience for repetitive digital tasks.

In insurance firms, banks, and logistics companies, vast armies of human workers spent their days moving data from one legacy system to another—copying from a PDF, pasting into a web form, clicking “submit.” RPA “bots” were designed to mimic these keystrokes and mouse clicks.

They could process thousands of claims an hour without error, 24/7. This was a profound evolution in the way help is provided.

The human role shifted from “doer” to “supervisor of the bots.”

Narrow AI: The Savant Helper

Simultaneously, we saw the rise of “Narrow AI” or “Weak AI.” Unlike the rigid scripts of RPA, Narrow AI uses machine learning to act intelligently in a very specific domain.

We developed systems that could analyze radiological scans to identify potential tumors faster and sometimes more accurately than human doctors.

We built algorithmic trading systems that could execute thousands of trades in the time it took a human trader to blink, leveraging patterns invisible to the naked eye.

We created recommendation engines (Netflix, Amazon) that helped us navigate paralyzing choices by predicting our own preferences better than we could.

These systems are incredibly powerful helpers, but they are brittle savants. A radiology AI cannot write a sonnet, and a chess-playing AI cannot drive a car. They excel in closed systems with clear rules and vast datasets.

They provided significant leverage in specific verticals but lacked general adaptability. They could optimize a supply chain, but they couldn’t tell you why it was breaking down if the cause was outside their training data (e.g., a global pandemic).

Up until very recently, this was the state of the art. We had faster hands (machines), faster calculators (computers), and specialized savants (narrow AI).

But the human was still the essential integrator, the decision-maker, and the glue holding these disparate tools together.

Phase Four: The Autonomous Horizon (The Rise of the Agentic Workforce)

We are now crossing the threshold into a new era.

The development of Large Language Models (LLMs) and multimodal generative AI has triggered a shift from reactive tools to proactive agents.

This is not just a linear improvement in technology; it is a qualitative change in the relationship between human and machine.

The defining characteristic of this new phase is Agency.

In previous eras, help was passive. A hammer doesn’t hit a nail until you swing it.

A spreadsheet doesn’t calculate until you input the formula. Even an RPA bot doesn’t run until it’s triggered.

An autonomous agent, by contrast, is given a high-level goal and empowered to determine the steps necessary to achieve it, execute them, learn from obstacles, and course-correct without constant human intervention.

We are moving from telling machines how to do something to telling them what we want done.

The Birth of the Synthetic Employee

Consider the difference between ChatGPT as it exists today and the emerging “agentic” workflows.

Today, you might use ChatGPT as a sophisticated assistant. You ask it to draft an email, write a block of code, or summarize a PDF.

You are the prompt engineer, the editor, and the project manager. You are holding the tool.

In the near-future autonomous model, you would give a directive: “Our e-commerce site is seeing a 15% drop in cart conversions over the last week.

Investigate the cause, propose three solutions, and implement the lowest-risk fix on the staging server for my review.”

To fulfill this request, an autonomous agent doesn’t just generate text. It must:

- Use Tools: It needs access to your analytics dashboard (GA4, Mixpanel), your server logs, and your codebase.

- Reason: It must correlate the data drop with recent server changes or external factors.

- Plan: Formulate hypotheses (e.g., “The recent payment gateway API update broke the checkout flow on mobile Safari”).

- Act: It might autonomously write a test script to reproduce the bug, then generate a code patch to fix it.

- Report: It summarizes its findings and awaits final approval.

This is no longer just “help.”

This is a synthetic colleague. We are seeing early examples of this in fields like software engineering, where experimental agents like “Devin” can take a bug report, browse the entire repository, identify the issue, fix the code, and run tests independently.

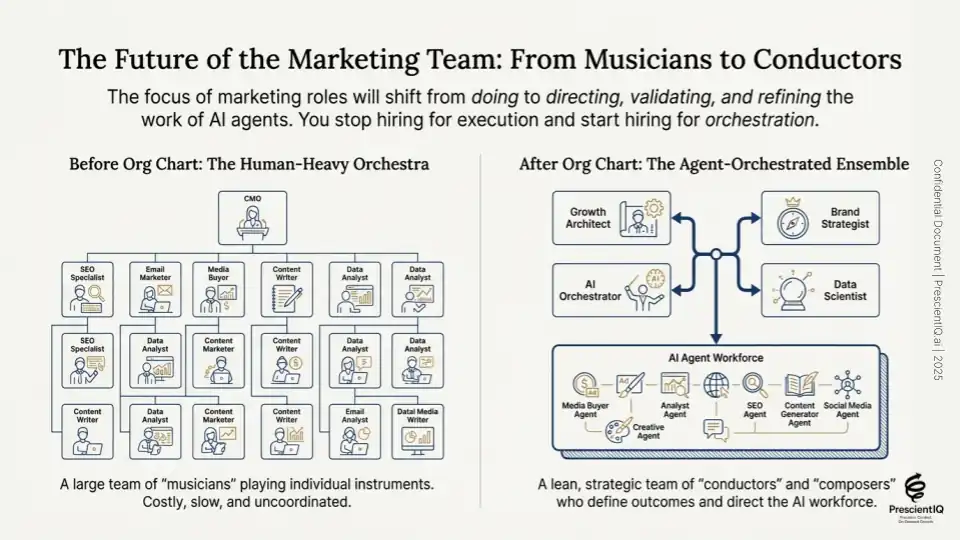

The Multi-Agent System: A New Organizational Chart

The future workforce won’t just be humans using AI; it will be humans managing teams of specialized AI agents that collaborate.

Imagine a complex task like launching a new product. In the future, a human manager might define the budget, the target launch date, and the product specs.

They then deploy a multi-agent system:

- A Market Research Agent scrapes the web to analyze competitors and track sentiment trends.

- A Product Design Agent takes those insights and generates initial mockups and feature requirements.

- A Legal Compliance Agent reviews the proposed features against regional regulations.

- A Project Management Agent coordinates the timelines of the other agents and flags bottlenecks to the human supervisor.

These agents will communicate with each other, hand off tasks, and debate optimal solutions in machine-speed environments.

The human role elevates to setting strategy, defining ethical boundaries, and providing the final “human judgment” sign-off on high-stakes decisions.

Implications: Redefining Human Value in an Autonomous World

The trajectory from flint axes to autonomous agents is a story of incredible liberation from drudgery, but it also forces a profound societal reckoning.

Every major evolution in “help” has caused temporary displacement and anxiety before creating new, unforeseen types of work.

The mechanization of agriculture freed 90% of the population from farming, leading to urbanization and the modern economy. The Industrial Revolution created the middle class.

The digital revolution created the knowledge economy.

The autonomous revolution, however, feels different because it targets the very cognitive skills we have long considered uniquely human.

If machines can write code, diagnose diseases, compose music, and manage logistics, what is left for us?

The Human Premium: Why vs. How

As we outsource the “how” of work to autonomous systems, the premium on the “why” increases dramatically.

The future human workforce will need to pivot sharply toward skills that remain stubbornly difficult to automate:

- Goal Setting and Strategy: An AI can execute a brilliant marketing campaign, but a human must decide which product to build and which market to target, based on intuition, culture, and values.

- Complex Ethics and Judgment: Autonomous agents will encounter gray areas. When efficiency collides with morality, human oversight is non-negotiable. We need humans in the loop to ensure that the “help” we receive aligns with our societal values.

- Empathy and Human Connection: In a world saturated with synthetic content and automated interactions, genuine human connection—in healthcare, education, therapy, and leadership—will become more valuable, not less. We will crave the authentic.

- Creative Synthesis and Novelty: While AI is getting better at mimicry and combination, true zero-to-one innovation—the kind of paradigm-shifting leaps that define human history—remains a human domain. AI can iterate on the known; humans dream up the unknown.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Symphony

The evolution of help is not a story of humans becoming obsolete; it is a story of humans transcending their limitations.

We used stone tools to break physical barriers. We used steam engines to break energy barriers. We used computers to break calculation barriers.

Now, we are using autonomous AI to break cognitive and executive barriers.

We are moving away from a world where we are limited by the number of hours in the day or the number of hands we can hire.

We are entering a world where we are limited only by the clarity of our intent and the ambition of our questions.

The transition will be turbulent.

Our economic systems, educational institutions, and social safety nets were built for an era of manual and cognitive drudgery that is rapidly coming to an end.

Adapting to an autonomous workforce will require policy innovation that keeps pace with technological innovation.

Yet, if history is any guide, the result will be a profound expansion of human potential. By offloading the mechanics of existence to an autonomous workforce, we may be free to focus on the art of living.

The ultimate goal of all this “help” has never been just to do more work faster; it has been to buy humanity the time and space to explore what lies beyond survival.

The tools have changed, but the quest remains the same.

PrescientIQ helps businesses build the next autonomous agentic workforce for unimaginable performance.